Leaders don’t always know what they think they know

An early public shaming shaped me in ways I am only now coming to understand. I think.

I was in first grade. It was mid March, and the teacher had us all sitting on the floor in a circle. She said that St. Patrick’s Day was coming up and asked if we knew what St. Patrick was famous for.

My hand shot into the air. I was the only volunteer. My self confidence swelled. I had a great answer, and I was pretty sure it was right.

The teacher called on me.

My five-year-old self proudly proclaimed, “He invented potatoes!”

A brief silence erupted, like in that instant that comes between the moment you see the explosion and the moment you feel the concussion.

Then came the uproarious laughter. Everyone rolled around on the floor in spasms, tears bursting out, their howls rattling the windows.

At least, that’s how my memory tells me it went.

Ever since, I’ve been reluctant to answer any question in public, even when I feel entirely confident I know the answer. In fact, the more confident I am in the answer, the more reluctant I am to speak out.

I always thought this was due to shyness, or to introversion. But I’ve learned that I’m not that shy, and I’m definitely not introverted.

It was instead due to a relentless second-guessing of my own knowledge. (Wait, one plus one really is two, isn’t it? Maybe… well… wait…)

Now, after listening to a fascinating podcast from Hidden Brain about the illusion of knowledge, I may never answer any question ever again. They basically confirmed that I do not actually know what I think I know.

What is the illusion of knowledge?

Illusion of knowledge, like the Dunning-Kruger Effect, will throw any smart person into a swirl of self-doubt.

Dunning-Kruger shows that people tend to overestimate their skill at things they’re bad at. Because we lack the tools to understand what greatness looks like, we don’t perceive the vast gap between our own skill and true expertise. The flip is also true—when we can fully appreciate greatness, the gap between our own competence and true expertise seems larger than it is.

The illusion of knowledge (or illusion of explanatory depth) is similar in that when we have the feeling of understanding of a thing, we treat that as equal to actually understanding the thing.

The podcast gives a very simple exercise to understand this phenomenon: Take something you think you understand from everyday life. They use the example of a flush toilet. Then, explain out loud to another person how that thing actually works.

Not how to operate it, but how it functions.

You may find that while you have a feeling of understanding, you have little actual knowledge.

We all do this, in many ways, all the time.

Most of us have a feeling of how Congress creates and enacts a budget, but if we have to explain it to another person? Not so much.

From kitchen timers to lighthouses to retractable seatbelts, we go through life thinking we have more knowledge than we actually do.

A lesson for leaders

Most senior executives have no idea how the systems they oversee work. They can’t know it all. It’s too complicated. They have to reserve their brain cycles for decisions.

Most employees want to look competent and smart to their bosses, so they hide how difficult many of their tasks actually are. They just want to produce the great product without exposing “how the sausage gets made.”

Now add in the concept of illusion of knowledge. Very likely, the senior executive feels a much greater understanding of how the company works than they actually have.

Put those things together, and you get a situation where the boss may be making what to them feel like very solid decisions, but to the employees feel out of touch, unrealistic, or even counterproductive.

But the employees can’t push back—they will look like lazy complainers! The boss doesn’t want excuses! So they just do whatever it takes to get the new request done, all the while eating away at the structure that holds the company together, like termites in the walls.

So what’s the answer for leaders?

Simple: Accept and acknowledge the fact that you do not have full knowledge of all the things your employees do in order to accomplish their tasks. This may feel backwards and vulnerable in corporate cultures that pretend the boss always has more knowledge, expertise, and technical ability than the workers.

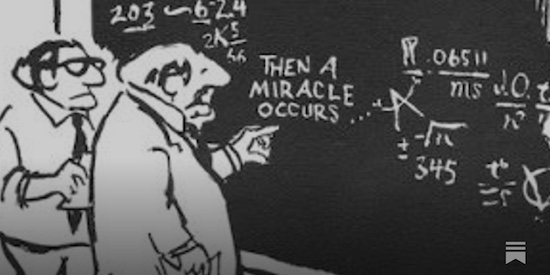

Before a big decision, try to explain how it will affect the existing systems in place. If you can’t explain it (no miracles allowed), then find someone who can.

Encourage a culture of transparency and truth rather than a culture of control and authority. When employees feel safe to speak truth, things improve. When they don’t, they say what you want to hear.

When I oversaw fundraising for a nonprofit, for the first couple of years I did not know how a check that was received in the mail moved through our system. Who deposited it? How did it get entered in the database? How was it acknowledged?

I knew these things happened and felt like I understood the processes. I could give you a system-level description like “now someone takes the check to the bank” and “now the donor information gets entered into the database,” but I could not tell you specifically how either of those things was done.

And when my development associate went on a three-week vacation out of the country, I made sure to learn every step of the process rather than put everything on hold for three weeks. Glad I did, too, because the COVID lockdown happened while he was on the other side of the world.

The promotion paradox

Leaders typically rise into leadership roles because they are highly competent. That can lead to arrogance. “I got promoted because I am smarter,” the leader thinks. “So I know more, and my decisions will be good, even if my employees disagree with them.” This is how great leaders make some pretty boneheaded and backwards decisions.

Try not to be one of those leaders. I’ve worked for a few. I am afraid that from time to time I made a few boneheaded and backwards decisions. At least one of those was due directly to an illusion of knowledge—I drastically underestimated how incompatible two systems were during a data migration because I thought I understood both systems deeply. The vendors of the two systems told me what I wanted to hear, not what I should have been told.

All this is to say, no matter how high you rise and no matter how much power you have, you don’t know everything.

You don’t even know most of what you think you know.

Connect with me

Schedule a consultation session now or drop me a line.

With Take Your Time Before Time Takes You, learn to make the most of every day through thought-provoking exercises and perspective-twisting stories. Get it now in paperback or ebook.

“It changed my life.” – TP, client

“A go-to guide for people who want to improve their lives but don’t know where to start.” – MJ, earlier reviewer

RELIT: How to Rekindle Yourself in the Darkness of Compassion Fatigue gives practical, actionable advice on avoiding and overcoming compassion fatigue and caregiver burnout. My chapter explains how I stay centered and focused so I can give every client my best, every time.

Download my chapter for free: Show up. Try hard. Be nice.

Or just go buy the whole book. It’s worth it.