Knowing when it’s time to stop

Knowing when it’s time to stop can be hard. When are you throwing good effort into something that should have ended already?

Examples:

- Staying in a job vs making a change

- Staying in a relationship vs breaking it off

- Trying to motivate someone else when they are digging in their heels

- Pushing ahead in a foundering business

- Clinging to an identity that’s no longer applicable

I’ve written before about action planning and quit criteria, but today I’m thinking about the feeling of being done. Not about achieving goals or meeting deliverables. Not about the easily measured. But about knowing when a thing is simply done.

I learned this through the act of writing poetry, but the lesson didn’t become clear until I was talking with a client three weeks ago.

This client sent me a revised and expanded essay he’d written and which we had talked about the previous week. He intended to post it on his blog and wanted my thoughts before making it public.

We worked through some things, but my biggest question for him was about how and why he’d expanded the conclusion. I said I thought it felt more complete in the original, before he added a whole new paragraph. For me, the added paragraph actually diluted the message and distracted the reader from his main point.

He agreed with me.

Is something ever truly done?

I’ve been to a lot of poetry open mic sessions, and I marvel at the people who fill five minutes reading a single poem. I often think it would have been more powerful and enjoyable if it were cut in half.

I typically write short poems. Few of my poems are longer than 30 lines. I’ll sometimes read three or four in a five-minute open mic. That’s not to say I’m a better poet than the long-winded writers. It’s simply a matter of style and preference. But it also reflects a certain level of clarity and trust in the doneness of a poem.

When I am working on a poem, I often get to a point where I feel the need to add a few more lines, but I struggle and struggle and struggle to add anything that actually improves the poem as a whole.

Then, all at once, I’ll have an epiphany: It’s time to stop. This poem is complete. It does not need any more. Relics was like that (included at the end of this post). I struggled for more than 20 minutes with it before realizing that adding to it would actually diminish it.

Head, heart, and guts align

What I realized when talking with my client was that we often fail to see when it’s time to stop because our head, our heart, and our guts are not all aligned. At least one is out of sync with the other two.

I’ve been through this feeling a number of times, and not just when writing. I have stuck it out longer than I should have in two different jobs, for example. I’m going through it right now wondering if three years is long enough for this blog.

Often it’s the head that has to catch up with the guts and heart. That was the case with my client. His heart and his guts felt that his essay was complete, but his brain was complaining that it was too short, that the reader needed the point hammered home more clearly, that citing a famous work would add authority and gravitas to his words.

Until a neutral third party (me) gave his brain permission to let go of those thoughts, he was unable to feel comfortable with the completeness of his essay. He couldn’t see it was time to stop.

Check in with all three parts

Coaches love to say that the biggest obstacle to success is that we get in our own way. This is also true in knowing when it’s time to stop.

Leave a job. End a relationship. Let go a friendship. Give up a fight. Finish a poem.

Sometimes, the problem is that you’re clinging to the wrong outcome, like when two people who should split up make “til death do us part” the most important part of their story. Sometimes, you’re focusing on the wrong criteria for “complete,” like my client with his essay.

Regardless, if you’re in a feeling of non-rightness, check in independently with your head, your heart, and your guts. One of them may be trying to pull you in a new direction. One of them may be digging in their heels.

Ask your head, your heart, and your gut questions like these:

- What makes this thing deeply important to me?

- What will spending more on it likely yield?

- How does my body feel when I think about spending more on it?

- How does my body feel when I think about stopping it?

- Does it feel more right to stop now or keep going a bit longer?

- Does it feel more profitable to stop now or keep going a bit longer?

- Do I feel more in control stopping now or keeping it going?

These are just suggestions to get your own imagination and self-interrogation going. In the end, you’re going to be the one who decides when it’s time to stop.

The poem I referenced

This is the poem I mentioned above, the one I struggled with for 20 minutes before realizing it was done. My brain kept insisting it was too short, that I hadn’t told the entire story. When my brain stopped focusing on the wrong things, it finally heard how strongly both my heart and gut felt it was time to stop.

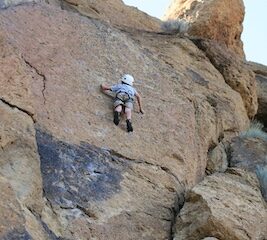

This poem was inspired by the photo, which I took in Martinez, California.

Relics

It rests in the rolling shallows,

this boat that once had a name

and a worthy purpose,

bumping against its crumbling dock

in the absent-minded rhythm

of the water’s eternal rise and fall.

Cracked and clouded windows

stare at us with a vacant scowl

like marbled eyes in the rest home

when other people’s grandchildren

tiptoe past the open door.

You and I meander the trampled grass,

reminisce around rocky inlets,

taste the spiced breeze of low tide.

We stroll along the polished train tracks,

their shiny new gravel peppered with

discarded, rust-crusted spikes.

Connect with me

Schedule a consultation session now or drop me a line.

Identify your core values with this free worksheet. Many of my clients find it surprisingly eye-opening. Get it here.

Download my chapter from RELIT

RELIT: How to Rekindle Yourself in the Darkness of Compassion Fatigue gives practical, relevant, actionable advice on avoiding and overcoming compassion fatigue and caregiver burnout. As a professional coach, I have to pay close attention to self-regulation and my own personal resilience. My chapter explains the things I do to stay centered and stay focused so I can give every client my best, every time.

Download my chapter for free: Show up. Try hard. Be nice.

Or just go buy the whole book. It’s worth it.