How not to jump to conclusions: ask what else could be true

Since conclusions were first invented, people have jumped to them. In this age of short attention spans, divisive politics, and culture wars, we’re getting better and better at it.

And by that I mean we’re getting worse and worse at critical thinking.

We have to process billions of bits of information every single second. So of course we train ourselves to look for clues that tell us immediately whether something is friend or foe, predator or prey, good or bad.

That’s useful if you’re scrolling TikTok and deciding whether to watch or skip a video. Or if you’re trying to survive in a wilderness filled with deadly perils.

In life, business, and relationships, though, jumping to conclusions is fraught with its own peril.

If you rob a store, you should expect to be shot

In a highly talked-about speech recently, a major candidate for leader of the United States said this: “Very simply, if you rob a store, you can fully expect to be shot as you are leaving that store. Shot!”

The bombast of course was about making sure that criminals don’t get away with their crimes. But it’s a good example of how jumping to conclusions could lead to wrong and disastrous actions.

For example: Someone is in a hurry and accidentally forgets to pay for something they put in their pocket. Their intent is to pay for the thing, but a mistake was made in their rush. This shopper is a mother of four with a baby in the car being minded by her oldest child, a 10-year-old. She’s on her way to attend a memorial ceremony for her husband, a soldier recently killed in an accident during a humanitarian action. As she hurries out of the store back to her car, a diligent vigilante sees that she robbed the store and shoots her.

Of course, both the original statement and my counter example are intentionally extreme and ridiculous, to make a point.

My point is that you may have one piece (or even many pieces) of 100% true evidence, but jumping to a conclusion without asking “what else could be true” can lead you wrong.

Seeing the world through a keyhole

It’s usually impossible to know every piece of information to fully understand something. In many cases, the best we can do is get to a level of confidence that is sufficient to believe a thing.

We all see the world as if we’re looking through a keyhole. We get only the information that we can see through that keyhole, then we make judgments and decisions as best we can.

The keyhole can represent a small set of relevant information, or it can represent a very short timeframe, or it can represent a set of biases in how the available information is interpreted. Or all three.

Rushing to judgment has always been a risky practice. The world today is encouraging us to do it more and more.

There’s an overwhelming amount of information coming at us all the time, but we can only process a tiny fraction of it. The world demands that we process it more and more quickly, forcing us into snap decisions. And nefarious forces profit from manipulating our decision process.

The result is bad decisions made too quickly on scant information with potentially disastrous consequences. Like investing in this guy. Or like perpetuating an untrue rumor without fact-checking it. Or like fueling hatred and discrimination by misusing a small set of facts and obscuring the bigger picture.

Pause and ask what else could be true

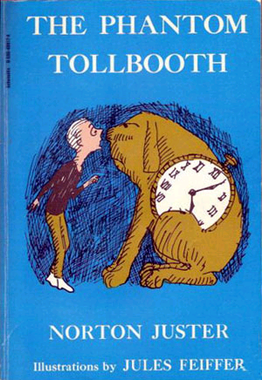

To avoid getting trapped on the Island of Conclusions like Milo did, simply pause and ask what else could be true.

This is one of my favorite questions these days. A lot of my individual clients need me to ask it of them, mostly in little situations where they’ve reached questionable conclusions. You think your coworker is working against you because they did something unexpected? You think you’re getting cut out of new projects because your boss has canceled their last two one-on-one meetings with you? Well, what else could be true?

Image grabbed from wikipedia

There are other versions of this question: What may I be missing? How does this information satisfy my personal beliefs? How may this data be skewed? Who profits from my decision?

The flip side… there’s always a flip side

It’s important to make sure you’re not jumping to bad conclusions because you have insufficient context, skewed data, or biased thinking.

It’s similarly important not to fall into analysis paralysis, which is where you become unable to make decisions even with a high level of confidence. Sometimes you need to trust your instincts and accept a certain amount of ambiguity. This is for another blog post, though.

Although some people are very much one type or the other (I’ve worked for both extremes), most of us fall in the middle. Even the very wise fall prey to both situations from time to time, however. We are all only human.

So remember to pause and ask yourself what else could be true.

I can help.

I work with top executives and middle managers to improve their leadership skills, their workplace culture, and the effectiveness of their teams. Also, I help individuals identify and achieve their personal goals. Would you like to become more aware, be more effective, be more empowered, and feel fully prepared for your next steps?

You can help.

Think of one person who would benefit from reading this post. Sharing is caring! Forward it to them right now. They will think you’re super smart and well informed.

Stay super smart and well informed.

Be sure to join my email list! Get notified of new posts here as well as new courses, books, and events from me both here and at Gray Bear Publications.

0 Comments