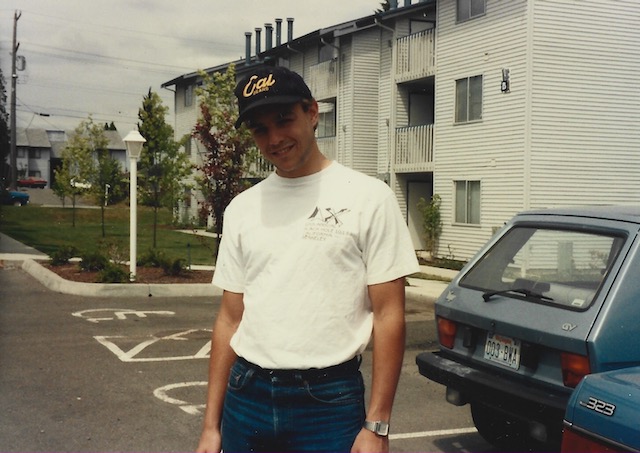

Quiet quitting before it was cool—Counting down to retirement in 1989

I have been told by a number of Millennials and Gen Zers, “I don’t want to spend my whole life sitting at a computer.”

They have this idea that “working a corporate job” is nothing more than “sitting at a computer.”

That’s like saying a rescue helicopter pilot is nothing more than “sitting in a cockpit.” While technically not incorrect, it’s far from complete.

When I graduated from UC Berkeley in 1989, I didn’t know much about the workplace. I knew engineers designed things and salespeople sold them, but not much more.

So, in a very tough market, I was grateful that UC Berkeley had a robust career support center. I applied to several jobs I’d never even heard of before, landing as a “change engineer” at Boeing in Seattle.

It was a fantastic first job for someone like me—I got to observe and learn in the middle of a mature and massively complex engineering project, with plenty of mentors I could turn to who’d been there for years.

It was my first exposure to hierarchy and bureaucracy, project dependencies, cross-functional design teams, real-world procurement and compatibility problems, and a lot more. I learned a ton.

The real world is far more complex than the classroom

I’ll never forget one of my earliest meetings, involving representatives from a dozen different departments, all trying to figure out how to fix one type of screw which was causing unexpected problems during flight tests.

To me, it seemed pretty straightforward at first: use a different type of screw. Right? The hardware store has gazillions of ’em.

I think it’s a truly incredible achievement of engineering.

Northrop B-2 Spirit – photo by Mike Mareen via Adobe Stock

But in reality, changing the type of screw meant new procurement contracts. Updated engineering drawings (the screw they needed had a different thread density). New testing procedures, then new tests. Changes to inventory processes, which might affect manufacturing schedules. (And, should they keep building new airplanes with the bad screws and retrofit later, or hold off for the new screws, which might delay everything?) And oh by the way there were already a few airplanes that would need retrofit in the field.

As a naïve, inexperienced kid who just got out of the classroom, I sponged it all up. I loved learning so much, even if the work itself was sometimes mundane and a little boring.

One of the most important things I learned in 13 months in that job, however, was that I never wanted to be in a position where I found myself counting down the years left to retirement.

How you arrive each morning reflects who you are

I was eager and punctual, so I was among the first in my group to arrive most mornings, though everyone got in roughly the same time and left roughly the same time.

We had an open office configuration in 1989—imagine rows of desks, three to a row, arranged classroom style in a big room where banks of tall filing cabinets provided the illusion of walls. Only the boss had an office.

It was also a secret project, so there were no windows. Every night we locked everything in drawers, and we kept the desk tops bare of everything except whatever we were working on in that moment. Each pair of desks shared a single telephone.

(Side note: Yes, I had a Secret clearance. No, I never handled any Secret documents.)

After my first few months, I was moved to a different desk between two older guys. Nice guys. Experienced. Good at their jobs, but not overly ambitious.

One of them, whom I’ll call Gene, had a ritual he went through when he arrived each morning.

Counting down 15 years to retirement

Gene was tall, lanky. Good softball player but didn’t look terribly athletic. Had a kind of wobbly gait.

Every morning he’d saunter in, pull out his chair, flop down in it, heave a heavy sigh, and say in his sort of wobbly way, “Out the door in 2004.”

This was 1989.

He was literally counting down to retirement eligibility 15 years in the future.

He’d planned it out—he’d have a nice pension if he stayed to his 30th work anniversary. He just needed to last that long. (I’m happy to say he did, though he switched projects.)

This “out the door in X years” attitude was not a feeling I identified with.

I was 22. I was newly engaged to be married. I had just moved to a new city. I was kicking off my career.

I didn’t want to start it by beginning a 30 year countdown to its end.

More than that, I realized I don’t ever want to stick around in a job where I feel like I’m counting down to retirement.

Like today’s Millennials and Gen Zers, I don’t want to “spend my whole life sitting at a computer.”

If I can’t continue to learn, grow, create, and stretch myself in new areas, then it’s time to find something else.

So I did. I was at Boeing only 13 months before moving back to the Bay Area to join a tech startup.

Being inspired to switch careers when necessary

These days, the word “career” doesn’t mean what it used to. In Gene’s day, a career was a straight line, starting with your first job and progressing mostly in a linear fashion until retirement. You cashed your checks, took vacations, put in for promotions.

These days, “career” looks more like a chaotic, colorful scribble than a straight pencil line.

I’ve made at least four fundamental career shifts, and I’ll make more if I ever feel like I’m starting to stagnate or losing my motivation. I’ve learned what drives me, and I am focused on using my talents in ways that inspire me, engage me, and allow me to be creative and help people.

None of those career shifts was planned out. My path through Boeing to software marketing to corporate responsibility to nonprofit fundraising to coaching was mostly about recognizing opportunity and stepping into it.

Knowing when to cut free, and knowing when to stick it out

Most of us can feel the need for change building up within us before the need becomes an urgency.

This is true in career as in life. We can see the writing on the wall sometimes long before we acknowledge it. We sense that a change is coming, or a change will soon be necessary, but change is hard so we often fight against it rather than embrace it.

There’s some wisdom in caution; you don’t want to give up a good thing without understanding the risks of change.

There’s also danger in comfort; when you fear the unknown, you may never know how much better things could be if you take a risk.

Gene understood what he was doing—he chose the comfortable path with the reliable story line. He was quiet-quitting before it was chic. He reached his goal, retired, lived a comfortable life that was right for him.

I understood what I was doing—I leapt into the unknown, and it led me to a series of jobs where I traveled the world, worked with amazing people, learned far more than I would have at Boeing, and stretched and grew in ways I’d never anticipated.

And a whole lot of that time has been spent sitting at a computer. In fact, I’m sitting at a computer as I write this.

Which would you have chosen?

If you were the third person sharing a row of desks with me and Gene, which path would you choose? Or would you try to forge a different path unlike either of ours?

In my mind, all paths are valid. What’s been right for me might not be right for you. What was right for your parents, your best friend, or your neighbor might not be right for you. And vice versa, of course.

I think the main key to progress is twofold:

- Understand who you are intrinsically and separate from what others think you should be, and

- TRY SOMETHING NEW.

If you’re young, new in your career, that second point is especially for you. Everyone tells you to follow your passion, but until you try a bunch of things you can’t really know what you’re passionate about. Very rarely does passion knock on your door—you need to seek it out.

And keep an open mind. A job where you “sit at a computer all day” may be a job that sometimes sends you to Tokyo, Lisbon, Frankfurt, and Paris. It may be a job where you get to move $50 million of other people’s money every year to charities all over the world, or where you create amazing art or music. It may be a job where you meet inspiring and amazing people.

If you’ve had some life experience, you may have done some work on the first of those two points. You may feel you know yourself really well.

I’ve never met anyone, though, who doesn’t change over time.

Honor those changes happening in yourself and your situation—examine and reexamine your values, your goals, and even your abilities in the new context of your home, work, relationships, and family as they change over time.

Getting too convinced of who you are can, over time, turn into beliefs that limit what your life could become.

How are you choosing your future?

What do you want to start doing, stop doing, or get better at? What has become stale or disappointing, or what has simply stopped being available to you? What kind of energy do you have for all the things filling your life now, and are those the things you want to be spending your energy on?

Despite Gene’s 15 year countdown ritual, none of us knows how much time we have left.

I think that sense of limited time is at the heart of young people’s reluctance to spend their lives “sitting at a computer.”

But it’s exactly that kind of limiting belief that holds so many people back and causes a vague sense of inadequacy and lost time.

0 Comments